AppleApple wants the world to know that it’s really, really serious about privacy. Accompanying the launch of the iPhone 6 and iOS 8 was a personal letter from Apple CEO Tim Cook about the company’s commitment to privacy and a new, revamped page about all-things-privacy on iDevices and a how-to guide for setting preferences to up your privacy if you’re an iUser. Apple has long used privacy to differentiate itself from the competition; back in 2010, Steve Jobssaid Apple “always had a very different view of privacy than some of our colleagues in the Valley. We take privacy extremely seriously.” Cook repeated the sentiment more strongly in his letter, taking direct aim at GoogleGoogle, saying Apple doesn’t build a profile of its users or “read their messages to get information to market to you.”

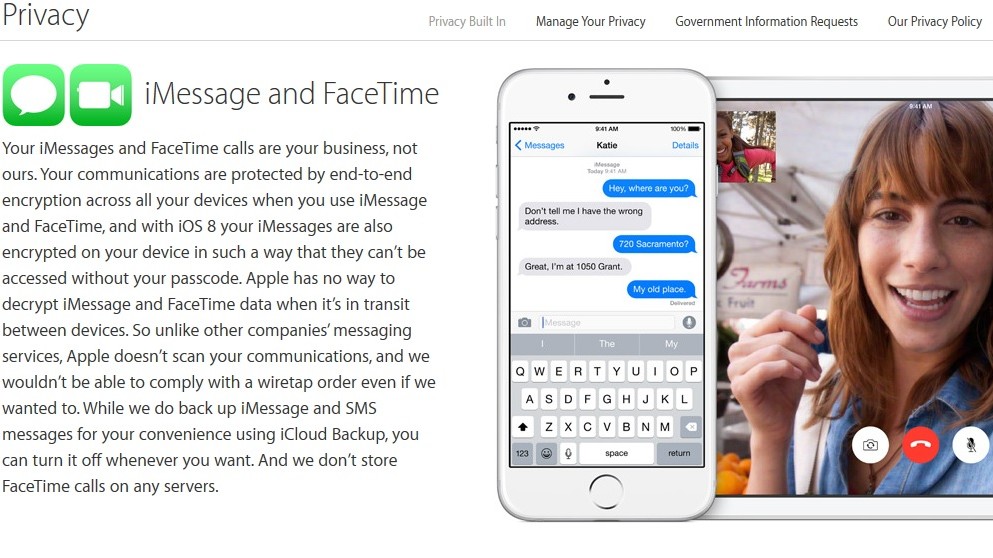

Apple is getting serious about privacy because it has to. It wants the iPhone to become the only thing you need beyond oxygen. The iPhone is not just for communication and web browsing anymore. It wants to track your health (with HealthKit), be your wallet (with Apple Pay), and control the devices in your home (with HomeKit). Depending on how personalized the iPhone 6′s vibration capabilities get, it could be your iSignificantOther. This is all set against the backdrop of concern about tech companies’ guardianship of our personal information amid the Snowden leaks. So Apple did something very smart. It announced that with iOS 8, the data encrypted on iPhones will only be able to be unlocked with your passcode. “Unlike our competitors, Apple cannot bypass your passcode and therefore cannot access this data,” Apple wrote on its privacy page. “So it’s not technically feasible for us to respond to government warrants for the extraction of this data from devices in their possession running iOS 8.”

So now, if law enforcement wants into your phone, they’ll need to get you to enter your passcode. One Apple competitor felt the heat. Google-owned Android quickly issued an “us, too!” announcement, saying that its next operating system will also encrypt data on smartphones by default for those using a passcode. Privacy advocates are thrilled. It’s not just about making it easier to protect civil liberties in the U.S. but exporting it to countries with restrictive governments where it will now be harder to get dissidents’ iPhone chats.

But former federal prosecutor and legal expert Orin Kerr was not thrilled. He says that if the po-po have a warrant, they should be able to get into a phone, and that Apple is making it harder for them to conduct lawful searches. People encrypting the content of their devices is not common practice now, but moving forward, it could become widespread, and law enforcement will have to force people to hand over or enter their passcodes in order to get evidence from those devices. That’s where the legal showdown will happen.

“If the government obtains a subpoena ordering the person to enter in the passcode, and the person refuses or falsely claims not to know the passcode, a person can be held in contempt for failure to comply,” writes Kerr.

That’s actually disputed legal territory. Back in 2012, Hanni Fakhoury, a lawyer at civil liberties group EFF, explored the issue of decryption as a Fifth Amendment issue. Is refusing to enter the passcode to your device the same as refusing to give incriminating testimony and “pleading the Fifth”? There is conflicting law on the issue.

A district court judge in Colorado ruled (PDF) that Ramona Fricosu could be forced to decrypt information on a computer seized by law enforcement in connection with a mortgage fraud case.2 But the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta ruled (PDF) that the 5th Amendment prevented the government from forcing a suspect in a child pornography investigation to decrypt the contents of several computers and drives seized by law enforcement.

In one case, the court ruled that law enforcement already knew what it wanted off the computer and could get it. In the other, the court ruled that law enforcement was trying to force the alleged child porn possessor to testify against himself by performing the decryption.

Kerr thinks the Fifth Amendment shouldn’t protect people against decrypting evidence that will be used against them, citing a 2009 case from Vermont, but suggests that if this turns out to be a problem, Congress should pass a new law upping the penalties — beyond a simple contempt charge — for people who won’t hand over their passcodes, or pass a law forcing tech companies to design their systems in such a way that they can bypass the passcode.

So expect legal firewords ahead….

Or not. It may be that the passcode doesn’t wind up protecting people as much as you might think from the headlines around Apple’s big move. Jonathan Zdziarski, a iDevice forensics expert, points out that his forensics software can still pull some data off a locked iPhone and that police could access much more if they seized a machine paired with your iPhone that would grant them access. Meanwhile security technologist Ashkan Soltani says that a majority of users likely use the iCloud to back up their devices, and Apple can hand over information from the iCloud to law enforcement if they have a warrant. “That’s still a huge hole,” says Soltani. He says it wouldn’t be hard for Apple to allow people to encrypt their iCloud files in the same personalized way their iPhone data is encrypted. “But they don’t do it for usability reasons. Because if a user loses their password, they lose their baby photos.”

As many a celebrity knows, it’s great if your iPhone is kept private, but if Apple can still hand the keys over to the iCloud, the government can get access to the evidence it wants.

Provided from: Forbes.